The Origin of Siglap

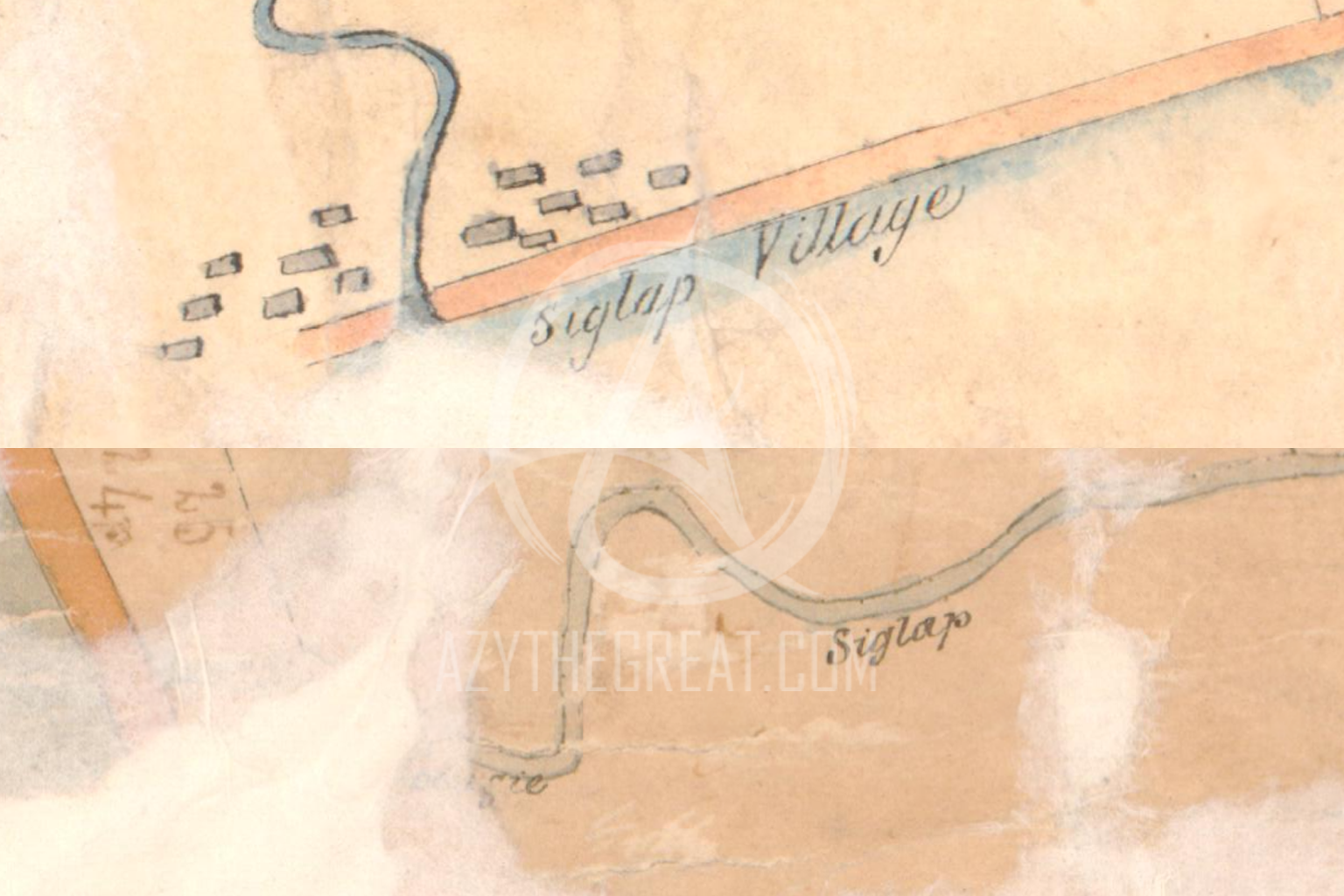

Kampung Siglap was a coastal settlement in eastern Singapore, with the earliest known records of the toponym Siglap as a single word appearing in the Singapore Free Press on 28 September 18431 and in two survey maps dated 1 November 18432 3.

From a linguistic perspective, Siglap is a phonetic rendering4 of Segelap, derived from the root -gelap5 and the prefix Si-, a variant of the classifier sa-/se- meaning “one”, “a”, or “entire”. The classifier aligns with a 1900s record on the National Archives of Singapore’s website describing the location as Tanjung Seglap6. While Siglap has other spelling variants, they are irrelevant to this article except for the hyphenated form Si-Glap7, which appeared in the 1977 A Report on the Fishermen of Siglap by the Siglap Community Centre Youth Group8.

(Siglap is not a transliteration, as this refers to converting the same word across different scripts, which does not apply to Malay-to-Malay conversions, nor is there any credible source that records Siglap in Jawi سݢلڤ on its own before 1843. It is also not an anglicisation, as the spelling does not follow English conventions.)

In Malay toponyms, the sa-/se- prefix no longer functions as a quantifier, as it does in words like seorang, sebatang, or sa-puloh ringgit9, but instead serves an idiomatic role. Therefore, while the dark one is a mistranslation that disregards this usage, and darkness that conceals is an exaggeration10, the meaning of Si-glap, Siglap, Seglap, or Segelap is simply dark11.

Malay toponyms with the sa-/se- prefix are often mistranslated. For example, Pulau Satumu is commonly rendered as One Tree Island, although it actually means Oriental Mangrove Island in the colonial context12 or Orange Mangrove Island in modern usage. In essence, Pulau Sakijang means Deer Island, Pulau Seking (or Sakeng) refers to either Longan Island13 or Hornbill Island14, and Pulau Sejahat means Wicked Island. A common misconception is to equate this with the “One” in names like One Raffles Place or One Fullerton, which is merely a branding device in English, unrelated to traditional toponymic principles. A known issue in toponymic interpretation is hyphenated forms, Si-Glap, where the hyphen was mistaken for a space, shifting the meaning of an idiomatic toponym to a personified name, Si Gelap, similarly to Si Comel, Si Kudung15, and Si Pitoeng16, or the familiar Si Senget known to former Siglap villagers17.

Where traditional toponymic principles are concerned, the words in Malay toponyms do not always convey a literal sense. For instance, while the Malay word “mati” means “dead”, in toponyms such as Sungai Mati or Sungei Belakang Mati, it refers to still or stagnant water. That said, Makam Segelap and Jembatan Segelap in Central Java use the word Segelap metaphorically to convey a spiritual or mystical atmosphere.

In the past we, received inquiries, including some from former villagers, about whether the theory of Siglap’s name deriving from a solar eclipse holds any merit. A total solar eclipse did occur on 4 March 182118. However, while the event was real, its connection to Siglap’s etymology contradicts linguistic evidence and traditional toponymic principles. A New Nation article dated 30 March 1980, titled Taking an amble through Kampung Siglap, could have been the genesis of the entire theory. This article reported that the village was founded sometime between 1819 and 1822 by an Indonesian migrant from Pontianak known only as Lasam19; the year 1821 appears to have been arbitrarily inserted to fill a historical gap, despite the absence of written records predating 1843.

It is likely that the 1977 spelling Si-Glap was used without recognising its idiomatic role, substituting the hyphen for a space and attributing a spiritual or mystical overlay. All these errors added layers to the theory despite the name Si-Glap having already been translated in other 1977 sources as dark place. The final addition is the non-credible identification of Lasam as a Sumatran prince; this suggests that the idea of him witnessing an eclipse and naming the place Si Gelap is derivative of the Sang Nila Utama legend, where a lion sighting was taken as an omen and used as the basis for naming Singapura. Equating the life of a real person with that of a legendary figure, who may also possibly have been a local adaptation of Sri Lankan folklore20, is intellectually insulting and disregards the cultural awareness of the area’s early inhabitants.

The solar eclipse theory is thus speculative at best and baseless at worst21 22. In fact, had Lasam arrived in Singapore at the precise moment of a solar eclipse lasting fewer than three minutes, the place would more plausibly have been named Gerhana, which aligns with placenames such as Kampung Wisata Gerhana Matahari in Sulawesi23 and Jalan Gerhana in Selangor, both of which reference eclipses. This linguistic precedent, appearing in both the Malay peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago, makes it highly unlikely that a migrant from Pontianak would have used the name Siglap.

How did the name Siglap come about?

The 1977 source translated Si-Gelap as a dark place, describing the area was once so heavily forested that sunlight could not penetrate through the thick canopy and the ground was shrouded in darkness. This aligns with John Edmund Taylor’s 1879 painting View along the Beach by Singlap, Singapore24, which shows dense inland forest. The description also corresponds to Desa Gelap, a farming village near a teak forest in East Java, and Kampung Segelap, an unofficial hamlet in Penaga Village, Bintan.

However, our own position is based on a survey map dated 21 October 184425, a year after the toponym’s earliest appearance, which shows a river near the coastal Siglap Village named Sungie Siglap. We believe that the name of the river gave rise to the name of the neighbourhood at large. This reflects a broader pattern across old Singapore, where village names were often derived from river names. In Malaysia, river names generally combine the word Ayer with a descriptor, such as Ayer Hitam and Ayer Kuning, which both refer to the colour of a stream. This convention appears in Singapore in the names of rivers such as Sungai Loyang, where the name refers to the brassy colour of the water caused by sediment and mineral-rich runoff.

East Java has a reservoir named Waduk Segelap, while in East Kalimantan (assuming that Lasam did migrate from Pontianak) there is also a river called Sungai Segelap, meaning Dark River. Other places in the world share similar names, such as the Dark River in New Zealand, the Dark River in Minnesota, and the Escuro River in Brazil, where escuro means dark in Portuguese.

Written by Hikari D. Azyure & Edited by Leonard Ng.

The Origin of Siglap is an original work by Urban Explorers of Singapore. Please cite/mention “Urban Explorers of Singapore” as the source if any of this material is used.

- The Free Press (Singapore), 28 September 1843, p. 2. ↩︎

- Plan of Siglap District No. VIII, National Archives of Singapore, 1 November 1843. ↩︎

- Plan of Siglap District No. VIII (alternate), National Archives of Singapore, 1 November 1843. ↩︎

- No credible written source independently records the name Siglap in Jawi as سݢلڤ before 1843. Therefore, Siglap is neither a transliteration, since that means converting words between entirely different writing systems, nor an anglicisation, because the spelling does not follow English conventions. ↩︎

- Richard James Wilkinson. An Abridged Malay-English Dictionary (romanized). 1901, xiv ↩︎

- Seglap (Tanjong Siglap), Singapore, National Archives of Singapore, 1900s. ↩︎

- Damien Mugavin. Suburban Singapore: Landscape of Change, October 2002. ↩︎

- Siglap Community Centre Youth Group. A Report on the Fishermen of Siglap. Ed. Chou Loke Ming, 1977. ↩︎

- Sa-puloh 1st Series Banknote Malaysia, 711Collection, 16 August 2010. ↩︎

- Jaime Koh and Stephanie Ho. Siglap, Singapore Infopedia, 18 August 2016. ↩︎

- Gelap as “darkness” in modern translation but this noun cannot exist without the adjective “dark”. ↩︎

- Origin: Pulau Satumun, Urban Explorers of Singapore, 30 July 2015. ↩︎

- Lydia Tomkiw. Indonesia Fruit Installement 6: Lengkeng/Kelengkeng/Longan, 9 November 2011. ↩︎

- The Origin of Pulau Sekeng, Urban Explorers of Singapore, 6 September 2019. ↩︎

- Norazmie Yusof and Minah Sintian. Exploring Brunei’s Oral Traditions: A Review of Cerita Lisan Brunei, November 2024. ↩︎

- Margaretha Cornelia van Till. In Search of Si Pitung: The History of an Indonesian Legend. July 1996. ↩︎

- Mohd Anis Tairan. Kampungku Siglap: Memoir Mohd Anis Tairan, 2010. ↩︎

- Fred Espenak. Catalog of Solar Eclipses: 1801 to 1900, NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center. ↩︎

- Taking an amble through Kampung Siglap, New Nation, 30 March 1980, pp. 10-23. ↩︎

- Folklore and the Construction of National Identity, Urban Explorers of Singapore, 9 August 2020. ↩︎

- False etymology, Wikipedia. ↩︎

- Gabriella Rundblad and David B. Kronenfeld. The Inevitability of Folk Etymology: A Case of Collective Reality and Invisible Hands, 2003. ↩︎

- Kampung Wisata Gerhana Bukit Ngata Baru, ANTARA Foto. ↩︎

- John Edmund Taylor. View along the Beach by Singlap, Singapore, 1879. ↩︎

- Plan Of The District Of Tannah (Tanah) Merah Ketchill (Kechil), NAS, 21 October 1844. ↩︎

Comments are closed.