The Origin of Pocong

The 2024 Indonesian horror, Do You See What I See, that I recently watched on Netflix, which tells a formulaic forbidden love story between a girl and a Pocong, isn’t the reason this post exist, but rather because of its English subtitle. In it, the name Pocong was being translated as demon, and corpse, but this is not right for two reasons. Firstly, the word demon in Indonesian is iblis or setan, while corpse is mayat. Maybe it was intended as a representation of Pocong being both, sure, but that leads to the second point: Pocong is a name, and names should not be translated, especially not when the character is the main antagonist of the film.

Such instances are not always bad thing. This one in particular actually made me wonder, and coincidentally reawakened a question I’d had for a very long time.

What does the word Pocong mean?

Pocong is a syncretic figure shaped by animistic and Islamic funeral rites, where loosening shroud knots frees the soul, while a bound one may lead to reanimation. In a modern context, Pocong reinforces Islamic burial practices among adherents in the Malay and Javanese communities. This shared belief between the two communities has resulted in distinct names for the same entity. Therefore, in this writing, I will approach segmentally by examine those within the Malayan sphere before exploring Javanese usage.

16 November 2014

This etymology-tracing journey begins with a 1903 anthropological report by Nelson Annandale1, who explicitly recorded the Malay Hantu Bungkus or Hantu2 Galas during his expedition to Perak and the Siamese Malay States. He glossed the names as Bundle or Package Spirit3 and noted that it had two forms: a bundle of dirty white rags and a true form as a white cat. Annandale described the white bundle form as a spirit that lies about at night in lanes leading to the cemetery, and should a person pass it who is afraid, it unrolls itself, twines itself round his feet, enters his person by means of his big toe, and feasts within on his soul, so that he becomes distraught and dies in convulsions, unless a competent medicine-man can exorcise it in time to save his life and reason.

Annandale’s report on this entity appears incomplete. He provides no description of the white cat, and the name Hantu Galas, or Bantu Galas as recorded by him, is unattested elsewhere. Since Hantu Galah is the closest phonetic match, it is likely that he mistakenly unified two distinct entities. The only connection I could make sense of Hantu Galah and the white cat comes from his description of the entity being one of the most dreaded of spirits in Pattani. The two forms he cited could have been a fusion between two beliefs, whereby white cats are typically seen as harbingers of good fortune in Thai superstition, while a white bundle symbolizes misfortune in Malay tradition. Furthermore, the entity known as Hantu Galah in Malay culture parallels Phi Taan Hua Khao in Thai folklore, suggesting a deeper cultural overlap left unaddressed by Annandale.

Regardless, Hantu Bungkus is unmistakably the Malay name for Pocong. While Annandale was aware of this, citing a very intelligent Malay in Upper Perak who explained that Hantu Bungkus was a corpse in its shroud, he made no mention of colloquial names such as Hantu Golek, Hantu Bantal, Hantu Bangkit, Hantu Gula-gula, Hantu Guling, and Hantu Gulung. Two of these names had already appeared prior to his 1903 report. In addition, Annandale also did not report on a well-attested typical Malay folkloric naming pattern that uses the class term Hantu, meaning spirit, ghost, or demon, paired with a descriptive term.

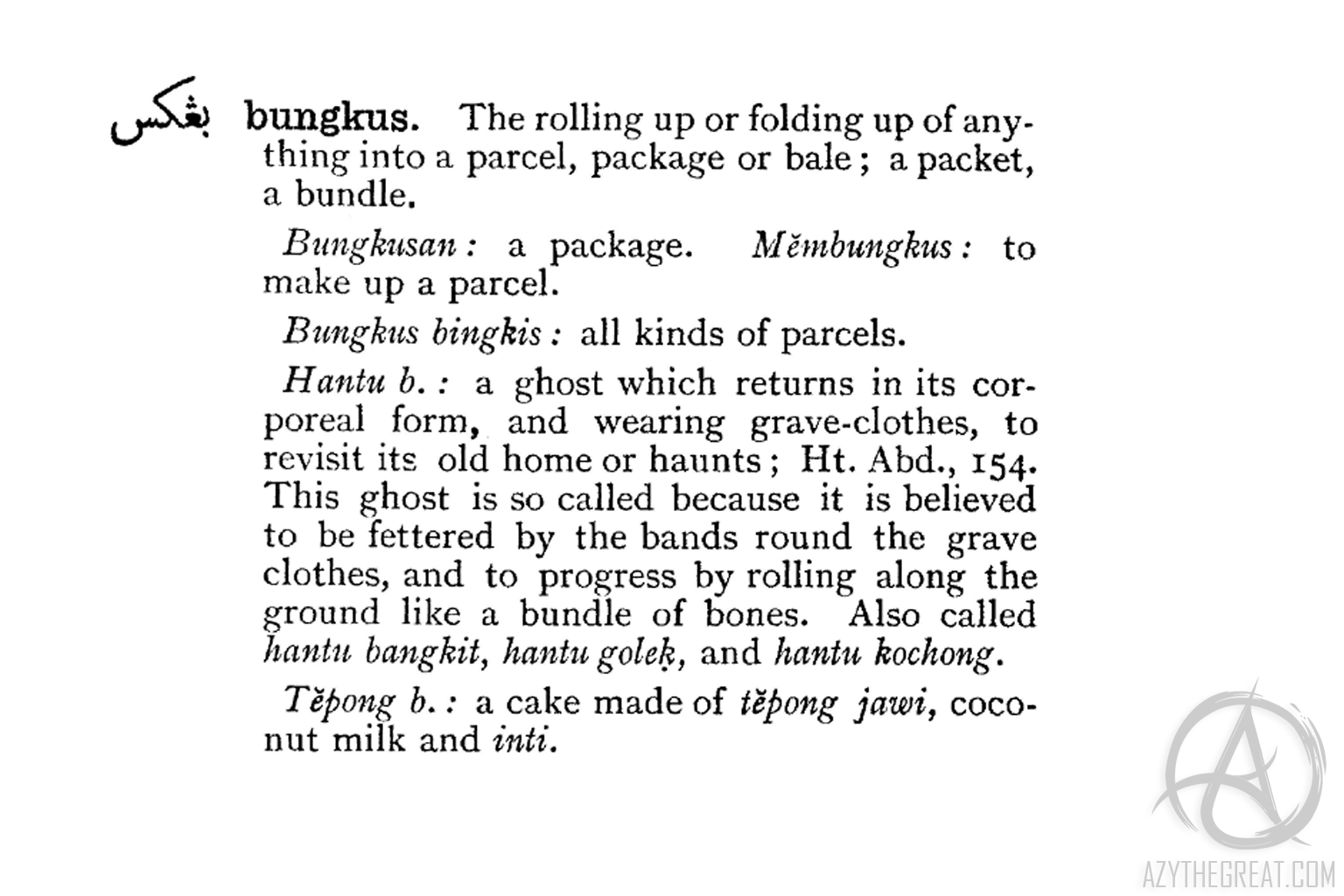

To illustrate the naming pattern, the word Bangkit, meaning to rise and stand or erected, reflects the motif of reanimation. The three words echoing movement are Golek, meaning easily swaying, easily shaken, or rolled; Guling (as a verb) in the Malay and Indonesian languages, meaning rolling, revolving, rolling over, or roll about; and Gulung, meaning to roll up or rolling up. The phrase Gula-gula, meaning sweets, refers to a twist-wrapped confection resembling a corpse in its shroud. In a similar vein are Bungkus, rolling up a thing (as package or parcel); Guling (as a noun) in Indonesian, meaning bolster; and Bantal, which generally means cushion or pillow, but in this case also means bolster.

This is not a real ghost caught on camera. Ghost don’t exist.

All lexical entries derived from Wilkinson’s Malay-English dictionary4. However, despite the inclusion of Malay dialect and Javanese terms labelled jav., the word Pochong or Pocong is curiously unlisted. The closest phonetic match is puchong, a generic term for bitterns such as Dupetor flavicollis, Ardetta cinnamomea, Ardetta sinensis, and Butorides javanica. The absence of the word in Wilkinson’s collection suggests that the name Hantu Pocong, or simply Pocong, likely entered Malay usage in the latter half of the twentieth century — or did it?

Bane, in her 2012 encyclopedia5 listed Hantu Kochong as a colliqual name of Hantu Bungkus. This name is particularly interesting. Tracing backwards, it appears in the 1932 Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 10, as Hantu Kochong (“sheeted ghost”). Further back, Wilkinson in 1908 glossed kochong as a long pyramidal cap; hantu k., a sheeted ghost which progresses over the ground by rolling along sideways. He also recorded Hantu Kochong in his 1906 Malay Beliefs6, a work published 3 years after Annandale’s 1903 Fasciculi Malayenses.

The fact that Annandale’s anthropological report only covered a tiny part of the Malayan peninsula strongly suggest that the name Hantu Kochong and Malay Hantu Bungkus were used concurrently during the same period. In addition to this, Skeat recorded kochong as a verb in his 1900 Malay Magic, however, noted it as the tying of a burial shroud’s ends using strips torn from the cloth7. Skeat’s recording of Kochong supports the possibility that Hantu Kochong was a known name in the early twentieth century.

The earliest record I found is tucked discreetly under bungkus in Wilkinson’s 1901 Malay-English dictionary, featuring the name Hantu Bungkus, with Hantu Bangkit, Hantu Golek, and Hantu Kochong in a single line.

Wilkinson also references Hikayat Abdullah (Ht. Abd) in this entry. While I couldn’t trace this specific source, I found the name Hantu Bungkus in Kassim Ahmad’s 1970 The Hikayat Abdullah8. This discovery not only hints at its presence in a much earlier 1849 Jawi print, Hikayat Abdullah (حکایت عبدالله) by Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir9, but may also identify the Malay Hantu Bungkus as being the first to have ever been used by the Malays.

Wilkinson did not label the term kochong with jav., however, given the presence of other Javanese terms in his dictionary and the influx of Javanese, Chinese, Tamil, Dutch, and even French loanwords in Malay, I hypothesised that kochong is not inherently Malay but of Javanese origin.

This hypothesis hinges on three points.

Firstly, given that Hantu Kochong and Hantu Pocong being the same entity, the 1956 Malay Spelling Reform held at the Congress of Malay Language and Literature in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, may have contributed to the lexical evolution, whereby Javanese kachong is absorbed into the Malay lexicon, morphs into classical pochong, and transits into the modern pocong we know today. The same k/p phonetic shift is evident between the name Kuntilanak, recognised in the Javanese sphere, and Pontianak, known across the Malayan region.

Secondly, the term kocong exist in Indonesian lexicon, glossed as hood. This term encompasses several literal meanings, such as kap (cap), tenda (tent), tudung (veil), kap mobil (car hood), and metaphorically, penjahat (a hooded villain). An interesting twist is that the traditional glutinous rice snack wrapped in leaves known as Kelupis, is also known as Kochong, with one variant folded into a triangular, hood-like shape10. Another interesting twist is that Wilkinson connects the term konchong to kochong. Konchong is the Indonesian name for a type of pork sausage11, generically called Lap cheong in Cantonese, encompassing a wide range of sausages tied to China, the Sinosphere, and Chinese diasporic communities. The phonetic similarity and sheer resemblance between Kochong and Konchong may have contributed to the corpse-in-shroud imagery, as both align with the Malay practice of naming entities after recognisable forms or traits. However, given the entity’s direct ties to Islamic burial rituals, Kochong is, in my view, the more accurate term.

Lastly, within traditional frameworks, Javanese folkloric entities do not utilise the class Hantu because the term itself is exclusive to Malay culture. This linguistic distinction is clear in Javanese Genderuwo vs Malay Orang Mawas, Javanese Kuntilanak vs Malay Hantu Pontianak, Javanese Wewe Gombel vs Malay Hantu Tetek, Javanese Kuyang vs Malay Hantu Penganggalan, and last but not least, Javenese Kochong vs Malay Hantu Bungkus.

Hikari D. Azyure, an urban explorer based in Singapore since 1995, is an independent researcher who has collaborated with others across academic and private sectors. His research centres on etymology and toponyms that may or may not be tied to folklore and mythology within the intangible cultural heritage field.

The basis of this writing derived from a 4 July 2007 article “Purpose of Pucong?”

That said, The Origin of Pocong is an original work by Urban Explorers of Singapore. Please cite/mention “Urban Explorers of Singapore” as the source if any of this material is used.

- Nelson Annandale. Fasciculi Malayenses: Anthropological and Zoological Results of an Expedition to Perak and the Siamese Malay States, 1901–1902. Vol. 1, 1903, pp. 21–22. ↩︎

- Annandale noted Bantu as a Malay word in his 1903 report, glossed as Independent Spirit, and listed it separately from the term Hantu. However, Wilkinson, in his 1901 and 1908 editions of the Malay-English Dictionary, glossed bantu as aid, assistance, to succour, to help. Bantu is a common word in Johor-Riau Malay. It is unclear whether the b- is a typesetting error, a metaphorical nuance of dialectal origin, or an initial consonant to the root antu, which parallels hantu in meaning. Despite the presence of bilmu (cf. ilmu, “knowledge”) and butan (cf. utan, “forest”), Annandale also wrote Bantu Bungkus even though Hantu Bungkus appeared elsewhere. I use Hantu in this writing to reflect a modern linguistic perspective. ↩︎

- It is unclear whether Annandale’s translation should be read as general or respective. Regardless, both still contradict Wilkinson’s definition of galas as “carrying on the back with a sling or support”. ↩︎

- Richard James Wilkinson. An Abridged Malay-English Dictionary (romanized). 1901, 1908, 1926 and 1961. ↩︎

- Theresa Bane. Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures. 2012, pp. 158-163. ↩︎

- Richard James Wilkinson. Malay Beliefs. 1906, p. 23. ↩︎

- Walter William Skeat. Malay magic: Being an introduction to the folklore and popular religion of the Malay Peninsula. 1900, p. 401 ↩︎

- Kassim Ahmad. The Hikayat Abdullah. 1970, p. 114 ↩︎

- Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir. Hikayat Abdullah (حکایت عبدالله). 1849. PDF via Sabrizain or Urban Explorers of Singapore’s GDrive ↩︎

- Search result for Kocong on Google Images. ↩︎

- Search result for Konchong on Google Images. ↩︎

Comments are closed.